The Fed gave half an inch

After the last FOMC meeting, I wrote, “Powell didn’t give an inch”, referring to his avoidance of acknowledging economic weakness. In this meeting, there were some acknowledgements of economic weakness (half an inch, let’s say), but Powell did his best to be dismissive of them to buy more time to see tariff inflation effects before lowering rates.

1. The statement. The FOMC meeting statement changed to acknowledge that growth in GDP had fallen from 2.8% in the second half of 2024 to 1.2% in the first half of 2025. At the June meeting (6/18/2025), the statement read,

Although swings in net exports have affected the data, recent indicators suggest that economic activity has continued to expand at a solid pace.

and yesterday it read,

Although swings in net exports continue to affect the data, recent indicators suggest that growth of economic activity moderated in the first half of the year.

A downgrade to the economy.

2. The dissents. Federal Reserve Governors Christopher Waller and Michelle Bowman dissented, preferring to lower rates at this meeting. There are only seven Federal Reserve Governors, and two of them dissenting (29%) is a big thing, something that hasn’t happened since 1993. It also happened in the period which looks uncannily like now, 1990, where Governors Martha Seger and John LaWare dissented to be more accommodative at the 7/3/1990 meeting, the month that the business cycle peaked before the recession. The Fed didn’t ultimately start cutting until late October 1990 after a long counter-economic pause amid an inflation scare and fiscal fears; just like now.

I thought only Waller would dissent, but Bowman’s agreement raises the profile of their argument which Powell said was clear and thoughtful (i.e., not politics to win the chair position). Powell indicated that they will publish a written statement in the next few days to explain their reasoning. It isn’t hard to guess what this will be because evidence abounds; core GDP (PDFP) has slowed for three quarters down to 1.2%, consumer spending has been negative over the last six months (and looks to be negative again in July from transaction data), something that only happens in recessions (piece coming soon on this), 5 of 6 NBER indicators were negative in May, housing indicators have cratered over the last year, consumer loan delinquencies are at recession levels, consumer debt growth is flat and recessionary, tariffs are a one-time price increase to look through, and private payroll growth (ex. government) is quickly approaching zero. Take your pick.

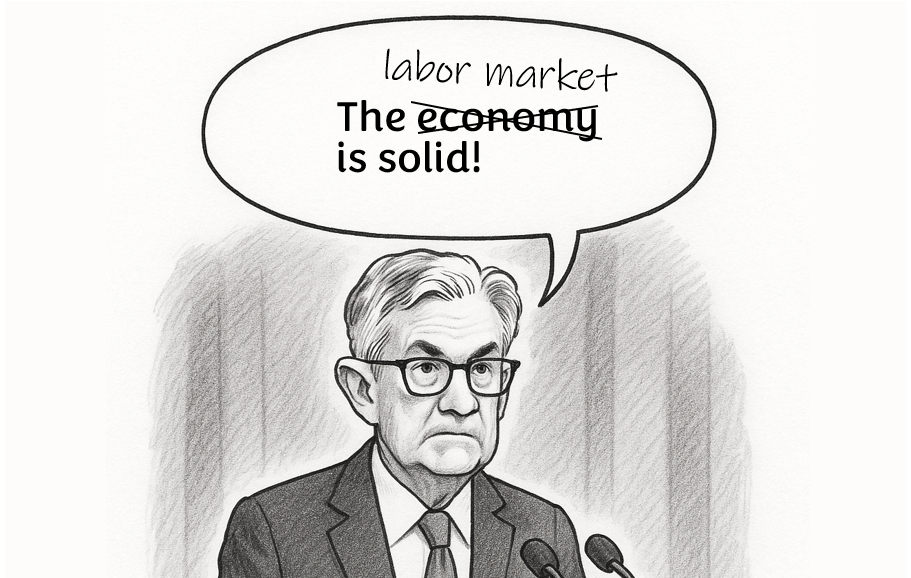

3. The press conference. About the only way one could tell things have changed since the last meeting was Powell reducing his oft-repeated phrase of “the economy is solid” to “the labor market is solid.” He leaned on this concept throughout, repeating a version of the idea that “yes, the economy has slowed down, but growth isn’t really a part of our mandate, and the labor market is still doing fine.” Note: because the Fed’s statutory mandate is stable prices and full employment, all growth arguments from the FOMC are spun into their impact on the labor market, but really, the Fed is concerned about the whole economy. Powell leaning into this distinction below shows him reaching for an out of acknowledging weakness. Some telling quotes:

Powell is unsure of how tariff effects will flow into consumer prices and thinks it is still too early to tell, exposing what I suspect is his true motive to not acknowledge the economic weakness that Waller and Bowman (and myself) are worried about.

I think you have to think of this as still quite early days, and so I think what we are seeing now is substantial amounts of tariff revenue being collected on the order of 30 billion a month, which is, you know, substantially higher than before. And the evidence seems to be mostly not paid — paid only to a small extent through exporters lowering their price and companies or retailers, sort of, people who are upstream, institutions that are upstream from the consumer are paying most of this for now. Consumers, it’s starting to show up in consumer prices, as you know, in the June report, we expect to see more of that. And we know from surveys that companies feel that they have every intention of putting this through to the consumer. But, you know, the truth is, they may not be able to in many cases. So, I think it’s — we are going to have to watch and learn empirically how much of this and over what period of time. I think we have learned that the process will probably be slower than expected at the beginning. But we never expected it to be fast. And we think we have a long way to go to really understand exactly how we will be. So, that’s how we are thinking of it right now.

Powell reminded that growth isn’t exactly part of their mandate, but said that the labor market is vulnerable,

Our two mandate variables, right, are inflation and maximum unemployment. Stable prices and maximum employment, not so much growth. So the labor market looks solid, inflation is above target, and even if you look through the tariff effects, we think it’s still a bit above target. And that’s why our stance is where it is. But as I mentioned, you know, downside risks to the labor market are certainly apparent.

Powell acknowledged that consumer spending has flatlined but was dismissive of it by citing other factors and hinting that it isn’t part of their mandate,

Consumer spending has been very, very strong for the last couple of years and had repeatedly forecasters, not just us, had been forecasting it would slow down. And now maybe it finally has. So, I would say, you know, if you talked to credit card companies, for example, they will tell you that the consumer is in solid shape and that spending is at a healthy level. It’s not growing rapidly but it’s at a healthy level and delinquencies are not a problem. Generally, if you look at the banks and when the banks talk about in their earnings calls, the performance of credit has been good. So, essentially you have a consumer that’s in good shape and is spending, not at a rapid rate. But it is true, and, again, right in line with what we expected, the GDP data that we got this week. So, and I think it’s still a little bit difficult to interpret because you have these massive swings in net exports which may also be affecting, you know, some of that can affect consumer spending as well. Look, it’s one of the data points that we pay most careful attention to. And there’s no question that it’s slowed. And we are watching it closely. But we also watch the labor market and the performance of inflation, those are our two variables that we are assigned to maximize.

Powell acknowledged that growth has slowed down but was dismissive of it because the labor market is still ok,

The GDP and PDFP numbers came in pretty much right where we expected them to come in. You got to look at the whole picture. So, certainly as I mentioned in my opening remarks, economic activity data, GDP, Private Domestic Final Purchases which we think is a narrower but better signal for future, for where the economy is going, has come down to a little better than 1%, 1.2%, I think, in the case of GDP for the first half. Whereas it was 2 1/2 last year. So that has certainly come down. But if you look at the labor market, what you see is by many, many statistics, the labor market is kind of still in balance. It’s things like quits, you know, job openings, and let alone the unemployment rate, they are all very, by many, measures, very similar to the way they were a year ago. So you do not see weakening in the labor market.

Powell is continuing to dance around economic weakness that looks an awful lot like the beginning of a recession to satisfy (most of) the committee’s outsized concern about inflation, having let inflation rise to 8% in 2022. To do so, Powell is painting himself into an ever-smaller corner that will soon get too small to work in. But the labor market’s continued strength (i.e., jobless claims falling for the last month and a half) allowed him to get away with it for another meeting. Waller and Bowman have this right; there is a business cycle to battle here, and delaying rate cuts now will make the upcoming recession worse — a nearly identical replay of what happened in the summer and fall of 1990.