Powell’s speech found the middle

Jerome Powell gave a much-awaited speech at the Kansas City Fed symposium at Jackson Hole this morning. Because of rising/hotter economic data, and a hawkish tone to the Fed lately, I thought he would lean hawkishly. He didn’t, but he wasn’t dovish either. Overall, the speech was well balanced between the two sides. Markets are keying off of the dovish shift from the last time we heard from him at the July 30th FOMC meeting (2yr down 10bps, S&P 500 up 1.5%), but I’m not sure either will stick. Key quotes are below, with hawkish passages in red, dovish in green.

On the labor market,

The July employment report released earlier this month showed that payroll job growth slowed to an average pace of only 35,000 per month over the past three months, down from 168,000 per month during 2024 (figure 2).2 This slowdown is much larger than assessed just a month ago, as the earlier figures for May and June were revised down substantially.3 But it does not appear that the slowdown in job growth has opened up a large margin of slack in the labor market—an outcome we want to avoid. The unemployment rate, while edging up in July, stands at a historically low level of 4.2 percent and has been broadly stable over the past year. Other indicators of labor market conditions are also little changed or have softened only modestly, including quits, layoffs, the ratio of vacancies to unemployment, and nominal wage growth. Labor supply has softened in line with demand, sharply lowering the “breakeven” rate of job creation needed to hold the unemployment rate constant. Indeed, labor force growth has slowed considerably this year with the sharp falloff in immigration, and the labor force participation rate has edged down in recent months.

Overall, while the labor market appears to be in balance, it is a curious kind of balance that results from a marked slowing in both the supply of and demand for workers. This unusual situation suggests that downside risks to employment are rising. And if those risks materialize, they can do so quickly in the form of sharply higher layoffs and rising unemployment.

On inflation,

The effects of tariffs on consumer prices are now clearly visible. We expect those effects to accumulate over coming months, with high uncertainty about timing and amounts. The question that matters for monetary policy is whether these price increases are likely to materially raise the risk of an ongoing inflation problem. A reasonable base case is that the effects will be relatively short lived—a one-time shift in the price level. Of course, “one-time” does not mean “all at once.” It will continue to take time for tariff increases to work their way through supply chains and distribution networks. Moreover, tariff rates continue to evolve, potentially prolonging the adjustment process. It is also possible, however, that the upward pressure on prices from tariffs could spur a more lasting inflation dynamic, and that is a risk to be assessed and managed. One possibility is that workers, who see their real incomes decline because of higher prices, demand and get higher wages from employers, setting off adverse wage–price dynamics. Given that the labor market is not particularly tight and faces increasing downside risks, that outcome does not seem likely.

Another possibility is that inflation expectations could move up, dragging actual inflation with them. Inflation has been above our target for more than four years and remains a prominent concern for households and businesses. Measures of longer-term inflation expectations, however, as reflected in market- and survey-based measures, appear to remain well anchored and consistent with our longer-run inflation objective of 2 percent.

On monetary policy,

Putting the pieces together, what are the implications for monetary policy? In the near term, risks to inflation are tilted to the upside, and risks to employment to the downside—a challenging situation. When our goals are in tension like this, our framework calls for us to balance both sides of our dual mandate. Our policy rate is now 100 basis points closer to neutral than it was a year ago, and the stability of the unemployment rate and other labor market measures allows us to proceed carefully as we consider changes to our policy stance. Nonetheless, with policy in restrictive territory, the baseline outlook and the shifting balance of risks may warrant adjusting our policy stance.

Notably he didn’t take the dovish tack that Mary Daly (San Francisco), Neel Kashkari (Minneapolis), and now Susan Collins (Boston) are using, that “inflation will rise, but we don’t have time to wait to find out before we cut”, but he also didn’t use Alberto Musalem’s (St. Louis) hawkish idea last week that only 50k jobs/month are needed to keep the unemployment rate from rising. Powell didn’t suggest anything about rate cut timing; the market filled that it in — the odds of a cut at the next meeting rose from 68% before the speech to 85% after.

But, because economic data has risen/gotten hotter in the last two months, I don’t think the debate between hawks and doves will be settled until economic data turns weaker again (watch the LDEI). Case in point, right after Powell’s speech, Beth Hammack (Cleveland) did an interview with CNBC. Her hawkishness wasn’t fazed by Powell’s speech, saying, “I’m squarely focused on the inflation side of our mandate.”

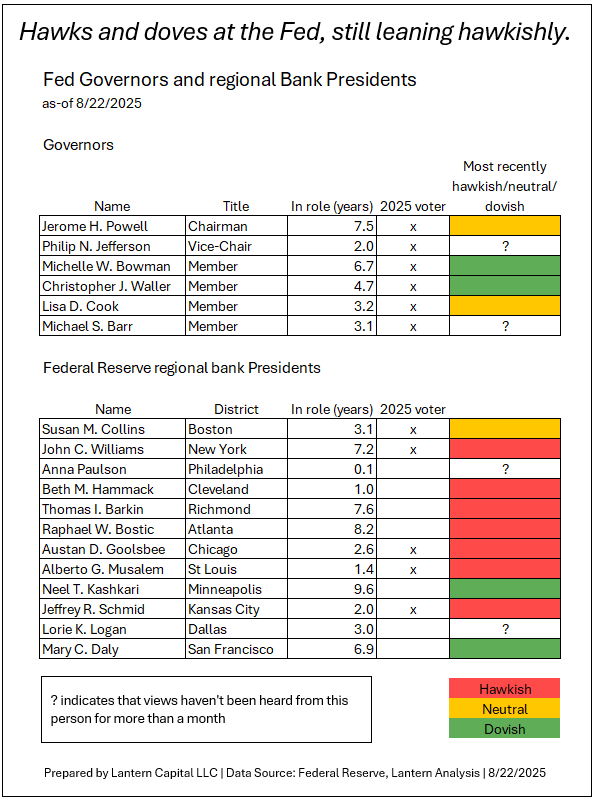

I’m sure weaker economic data is coming given the point in the business cycle, but two months of stronger consumer spending, higher services inflation, and a hot PPI are tilting the overall Fed hawkish for now. Of the 11 voters on the FOMC, by my assessment, there are two doves, three neutral, four hawks, and two unknowns (table below). Of the whole group (18 Governors and regional bank Presidents), there are four doves, three neutral, seven hawks, and four unknowns — still a lot of red. Powell’s intention today was not to lean one way or the other, but to strike a compromise between hawks and doves.