Five reasons to expect some softening from the Fed tomorrow

Last month, with economic data weakening quickly and Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller lobbying for a cut, I expected the Fed to cut rates at the FOMC meeting this week. But upon the strong payroll report on July 3rd, I wrote in my semi-weekly LDEI update,

I can’t imagine they will cut in July now, priced at just a 4.7% chance in Fed Funds futures.

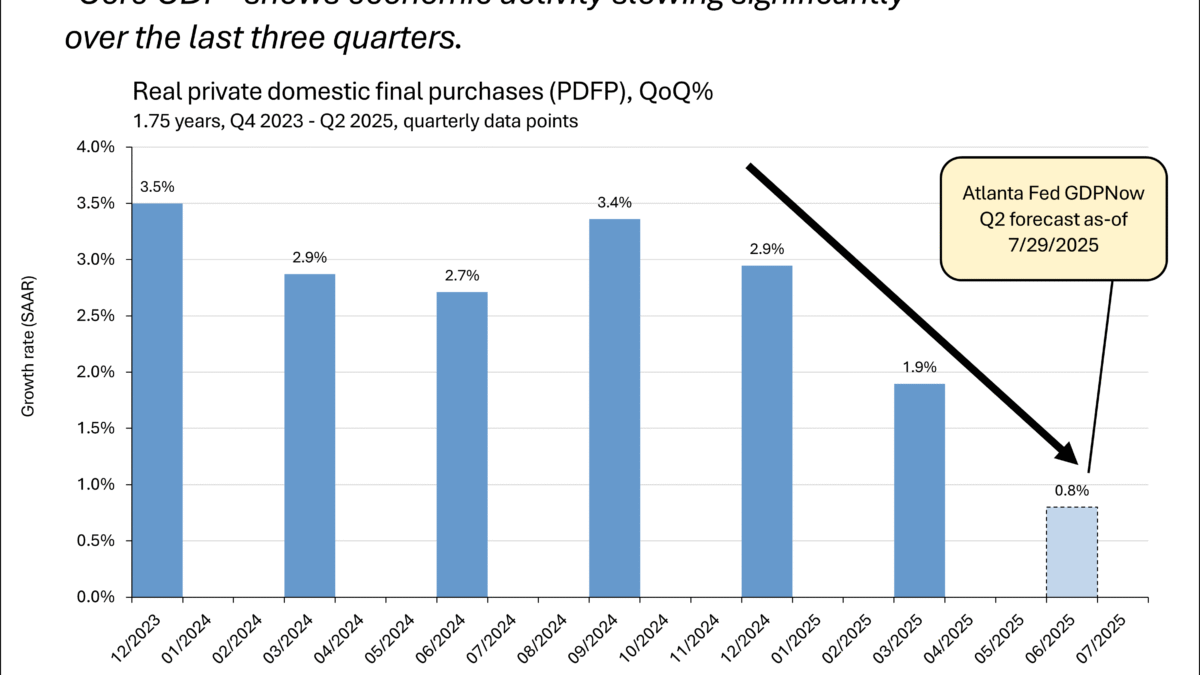

Since then, economic data has improved further (LDEI, oval in chart below) making a rate cut tomorrow even less likely.

But even though the Fed won’t be lowering rates at this meeting, there are five reasons to expect some softening towards cutting rates from Powell’s press conference.

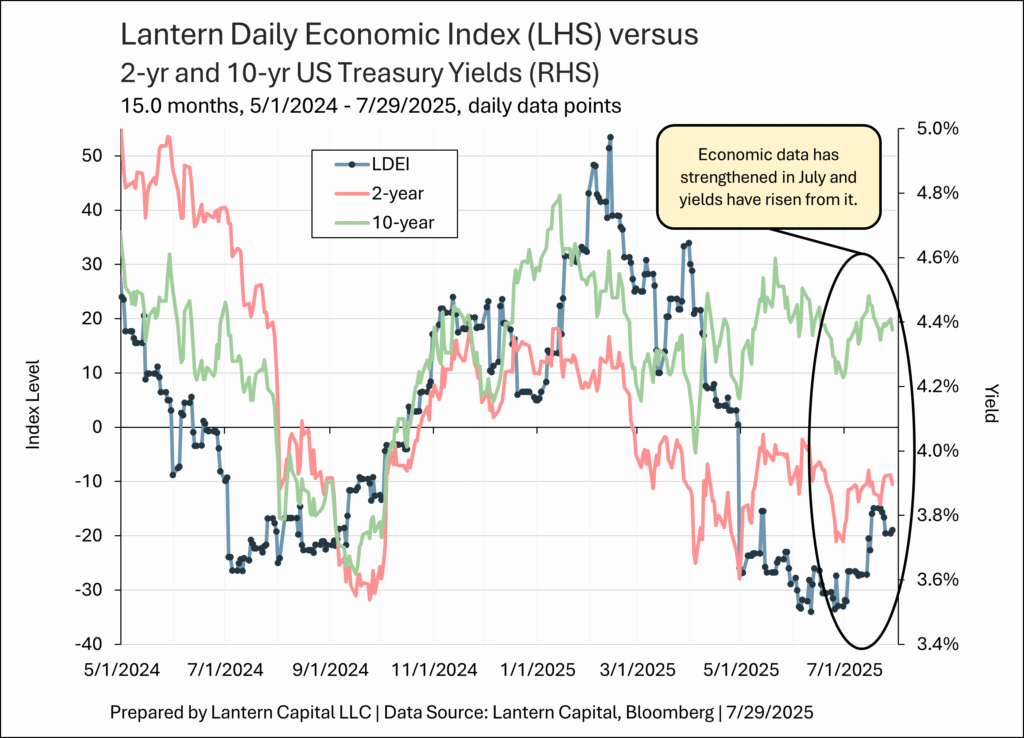

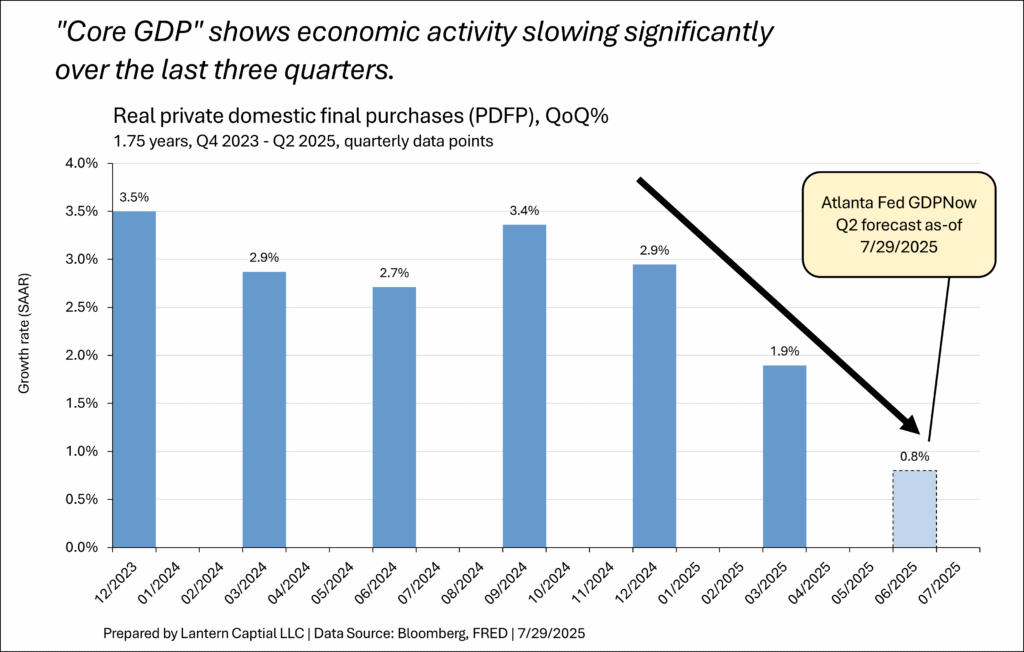

1. PDFP. Jerome Powell frequently mentions private domestic final purchases (PDFP) in press conferences as the Fed’s preferred signal within the GDP report. PDFP excludes foreign trade, government activity, and inventory investment; isolating private domestic demand which is the part economists are most concerned about falling in a recession. This measure is closer to the 6 monthly indicators the NBER uses to date recessions, the LDEI, and the Conference Board’s coincident indicator index which have all shown recent weakness. Positive PDFP was crucial to seeing that the US economy wasn’t in a recession in the first half of 2022 when Q1 and Q2 headline GDP were consecutively negative and was important earlier this year to seeing that headline GDP understated growth because of tariff pre-buying activity. Think of it as “core GDP”. Powell mentioned it in four of the last eight FOMC meetings:

a. 7/31/2024: “Private domestic final purchases, or PDFP—which excludes inventory investment, government spending, and net exports and usually sends a clearer signal of underlying demand— grew at a 2.6 percent pace over that same period, the first half.”

b. 12/18/2024: “I think it’s pretty clear we’ve avoided a recession. I think growth this year has, has been solid, it really has. PDFP, private domestic final purchases, which, which we think is the best indicator of private demand, is looking to come in around 3 percent [real growth] this year. This is a really good number. Again, the U.S. economy has just been remarkable.”

c. 5/7/2025: “I mentioned private domestic final purchases, which doesn’t have inventories, government, or—inventories, government. Anyway, it’s a cleaner read on private demand. But that, that, too, probably was flattered a little bit by—you know, by strong demand for imports to be tariffed. So that might overstate. It’s a really good reading, 3 percent PDFP in the first quarter.”

d. 6/18/2025: “Private domestic final purchases, or PDFP, as we call them—which excludes net exports, inventory investment, and government spending—grew at a solid 2.5 percent rate.”

Q1 PDFP was revised down to 1.9% since that last Powell quote reducing how solid the economy is, but more importantly, it is projected to be just 0.8% for Q2 upon its release tomorrow morning which would corroborate the large slowdown in the LDEI since mid-February. It will likely show a third successive quarter of slowing growth and Powell will have to address it.

2. Consumer spending. Real consumer spending, one of the six indicators the NBER uses to date recessions, fell over the first five months of this year, and is expected to extend that decline to six-months upon an update released on Thursday. Real consumer spending hasn’t declined over five months (or six) since 2020 during the pandemic and before that, since 2009 after the Great Financial Crisis. While the labor market has largely held up so far (initial jobless claims improving over the last month and half), its main economic importance is that it predicts consumer spending (Okun’s law). If the consumer is already slowing spending without the labor market shrinking (and a trend that began in January, well before tariffs), what will spending look like once the labor market weakens in earnest? An important reason for the Fed to be concerned now.

3. Tariff levels are becoming more settled; inflation is still not running away. Most of the largest US trading partners have made trade deals and settled on a tariff rate for exports into the United States, including the biggest, the EU, at 15% this week. The Fed is very interested in where the effective tariff rate (ETR) will land to model what it’s inflation impact will be. The ETR appears to be settling somewhere in between 15% and 20% (18.2% as of yesterday from the Budget Lab at Yale). Each trade deal removes more uncertainty. From Waller’s simple tariff inflation model, an 18.2% effective tariff rate, with consumers absorbing one-third of that price increase, and 10% of consumer spending on foreign goods, results in a one-time tariff price increase of 0.6% (.182 * .033 * .1); not the end of the world.

Also, Truflation, which correlates highly to headline monthly CPI but is available up-to-date and daily, still doesn’t show an inflation surge around the corner with most of the data in for July. It is hovering right around 2%.

4. Dissent. By all accounts, Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller will dissent tomorrow in favor of lowering rates. Some think Michelle Bowman will dissent too based on her June 23rd comments on Fed policy, but it is hard to know how her thinking has evolved from that month-old speech. Even with one dissent, Jerome Powell must acknowledge Waller’s economic concerns. It is important to note that Waller isn’t benignly suggesting to cut rates if inflation behaves like Bowman did, he is overtly concerned about the economy.

5. Timing. As of the last FOMC meeting, the median FOMC participant expected to cut rates two more times this year. After tomorrow’s meeting, that leaves just three meetings to do so. In an article previewing the Fed meeting published last night, Wall Street Journal Fed beat reporter Nick Timiraos wrote about comments from former Dallas Fed bank president Robert Kaplan,

What is dividing colleagues right now reflects differences in risk management—how much weight to give the possibility of moving too early versus too late, and which type of mistake would be harder to fix. “If you make a decision where you’re a meeting or two late, that’s a tactical issue, which is manageable,” said Robert Kaplan, who was Dallas Fed president from 2015 to 2021. “You want to avoid mistakes where you do something where it might take a year or two to then rectify the situation.”

The Powell Fed often operates “like a supertanker” that “doesn’t turn on a dime,” said Kaplan, who is now at Goldman Sachs. That reflects an institutional prerogative to manage expectations and limit instability rather than react quickly like business executives or traders. Given the unclear inflationary impacts of tariff increases, “the Fed has been wise so far to be cautious,” he said. Still, Kaplan said if he were in his old job, “I’d be getting myself in a position now to start turning the supertanker” so that the Fed could cut “with conviction in September” if warranted.

Kaplan sounds pretty hawkish here but still sees the need to position for the possibility of lowering in September now. Overall, with these five reasons, Powell should gently steer public expectations towards the possibility of a September rate cut without committing to one tomorrow.